Sanjay

Sharma

The Indian Express, 8 February 2014

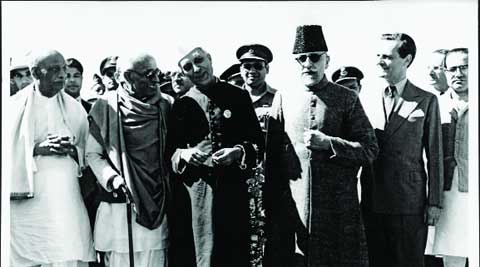

In the words of the

historian Mushirul Hasan, this book employs an “unconventional form of

storytelling, which seeks to provide the thrill and opportunity of being a

historian and an explorer” to each reader. Through a motley selection of

archival documents like photographs, personal letters, official orders and

speeches (some in Urdu) and colonial records (several classified as

“confidential” and “secret”), the book tries to throw light on some

lesser-known aspects of the life and times of Maulana Abul Kalam Azad, India’s

first education minister.

The dominant image of

Azad has been that of a secular nationalist Muslim — the sherwani, beard and

the topi doing their bit. By all accounts, he was not a secular nationalist to

begin with. He could not be, as the description carried little meaning till the

second decade of the 20th century. Indeed, one can plot the evolution of this

uniquely Indian identity by closely following Azad’s personal and political

journey from his birth in Mecca in 1888 to his final resting place in Urdu Park

in front of the Jama Masjid, Delhi, in 1958.

Like many illustrious

contemporaries, Azad’s public life began in print journalism, where his Islamic

education and learning acquired an anti-imperialist edge. He came in direct

conflict with the colonial regime, especially with his eloquent writings in the

Urdu weekly Al-Hilal, which he started in 1912. Fascinating Home and

Intelligence department documents presented in this volume clearly bring this

out, with one in 1916 describing him as “an extremely able and dangerous man

with very pronounced Pan-Islamist views.”

Predictably, Azad was

drawn to the Khilafat movement, which could have limited him to Muslim issues.

But the Non-Cooperation Movement and Gandhi’s Congress took him to a pan-Indian

path instead of a pan-Islamic one. The scholar-preacher was transformed by the

tide of mass movements. The transformation was not lost on Gandhi, who wrote

about him in Young India on February 23, 1922: “What a change between 1919 and

1922 — nervous fear of sentences and all kinds of defences in 1919, utter

disregard of sentences and no defence in 1922”. A year later, he was elected

Congress President at the age of 35 and as Hasan writes, “he was looked upon, in

spite of his youthful years, as one of the elders of the Congress”.

The

post-Non-Cooperation years of the 1920s saw a resurgence of communal clashes

and Azad was invariably drawn to the question of Hindu-Muslim relations.

However, he did not approach the burning issue exclusively with the clinical

tools of western modernity. Instead, he revisited Islam and found ideas and

inspiration for a theology of “multi-religious cooperation” and the

“transcendental oneness of all faiths”. He went on to situate himself in the

rich composite legacy of Islam that he fervently advocated in the 1940s, which

were laced with separatist Islamist forces. In this, he received the trust of

the Congress and led the party for an interrupted spell from 1939-46. Azad’s

commitment to the idea of an inclusive India grew firmer and his rejection of

the two-nation theory invited charges of him being a leader of token symbolic

value and just a titular head during the negotiations with the Cripps and

Cabinet Missions.

We do not know enough

about how Azad dealt with this because despite spending 10 years in jail, he

did not write as much as some of his prolific contemporaries. Nehru, in fact,

even lamented Azad’s limited written output while acknowledging his learning

and wisdom. Hasan makes an interesting observation: Nehru and Azad were unlike

in many ways and despite coming from diverse backgrounds came to share each

other’s “exuberant inclusiveness”. Azad even succeeded in rubbing off most of

Nehru’s “rough edges”, though he was considered to be quite polished. That is a

lesson for contemporary Indian political culture.

Azad spent the last

10 years of his life as the first education minister of the young republic.

Post-1947, he immersed himself in the task of nation building by pioneering new

institutions like the Indian Council for Cultural Relations, the University

Grants Commission and the Sahitya Akademi.

Some documents here

are gems, sure to delight those interested in the formative years of free

India. For instance, there is a note dated July 11, 1950, regarding the singing

of the national anthem in schools and colleges, and another written on 22

April, 1953, to C Rajagopalachari, emphasising that the Constitution and

Islamic law should uphold the equality of daughters in succession, in the

absence of sons. However, several of these crucial documents are in Urdu.

Translations would have helped.

This book is much

more than what its title suggests. Azad’s life, letters and career give us

further insight into the texture of colonial state power, the arguments its

functionaries manufactured to ban Azad’s early “seditious” writings and to deny

him a passport at one stage. Azad’s own persona needs to be rescued from the

burden of the clichéd meanings of “pluralism” and “secular nationalism”. He was

more than that: someone who richly contributed to the evolution of a rooted

Indian liberal tradition and dared to face the dilemmas of given traditions and

modernity.

(Sanjay Sharma teaches at Ambedkar University, Delhi)

कोई टिप्पणी नहीं:

एक टिप्पणी भेजें