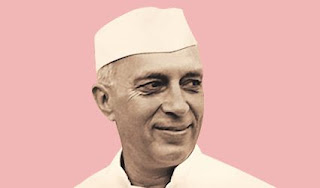

Indian Democracy: Debt to Jawaharlal Nehru

Sunday 1 June 2014

Mridula Mukherjee, Mainstream, VOL LII, No 23, May 31, 2014

The Nehru era ended half-a-century ago, bringing to a close the age of innocence and excitement marked by the epic struggle for freedom’s tryst with destiny and the first phase of independent India’s efforts to redeem that pledge. And yet, the strong roots sent down by the founders of the Indian nation have ensured that we just concluded our sixteenth general election with an electorate of over 800 million of whom a staggering 64 per cent cast their votes. And yet again, power has been transferred without any hiccups or hesitation from the outgoing government to the incoming one.

Indeed it is a measure of its success that we forget to notice how remarkable this achievement is, and celebrate it, for we are so used to taking it for granted. But we only have to look around us in South Asia, at Nepal, Pakistan, Bangladesh, Sri Lanka, Maldives, Myanmar, and at South-East Asia, and East Asia, and West Asia and Africa, to see how exceptional it is. Scholars sometimes quibble over whether it is a formal or substantive democracy, forgetting that the very survival of democracy is an achievement.

We owe this undoubtedly to the millions who fought the battle for freedom from autocratic and undemocratic colonial state and the feudal and monarchical princely states to set up a republic in which they would be citizens and not subjects any more. They were led by a galaxy of leaders of such exceptional ability that it is indeed unfair to single out any one. And yet, the name of Jawaharlal Nehru cannot but be singled out since destiny chose him as the one who shouldered the major part of the task of building and shaping democratic institutions and democratic habits and demo-cratic culture in the newly independent India. Mahatma Gandhi was removed within six months on independence by the cruel hands of an assassin who did not want a secular democratic India. Sardar Patel, who had stood firmly by Nehru’s side in steering the republican Constitution to its goalpost through many winding paths, and had unhesitatingly cracked down on the forces responsible for the Mahatma’s murder—banning the RSS and sending 25,000 RSS workers to jail—had also died by 1951. So it was left to Nehru as the first Prime Minister and pre-eminent leader to nurture the infant of Indian democracy and bring it to maturity.

For Nehru, democracy and civil liberties were absolute values, ends in themselves, and not merely a means for bringing about economic and social development. There was in him what his biographer S. Gopal has called “a granite core of intellectual and moral commitment to democratic values”. “I would not,” Nehru said, “give up the democratic system for anything.”

Nehru was a firm believer in freedom of thought and expression, and particularly freedom of the press. He believed that even the demands of public safety should not normally encroach on these freedoms. During the days of the freedom struggle, he had founded the Civil Liberties Union. It was he who took up and popularised the demand for a Constituent Assembly to draft India’s Constitution since 1935-36. He was also the main campaigner for the Congress in the 1937 elections.

His commitment to parliamentary democracy is shown by the seriousness with which he treated the business of elections. He did not use the excuse of the partition of the country and the consequent communal violence and influx of refugees to postpone elections. On the contrary, he was impatient to go to the people and was unhappy that the elections could not be held earlier. He converted the election campaign into a referendum on ‘the idea of India’, challenging the communal forces responsible for the Mahatma’s assassination who had been demanding a Hindu Rashtra.

In the election campaign for the first General Elections of 1951-52, Nehru travelled some 25,000 miles and addressed in all about 35 million people or a tenth of India’s population. The following extract from a letter he wrote to Lady Mountbatten on December 3, 1951 shows how much he enjoyed this hard work:

Wherever I have been, vast multitudes gather at my meetings and I love to compare them, their faces, their dresses, their reactions to me and what I say. Scenes from past history of that very part of India rise up before me and my mind becomes a picture gallery of past events. But, more than the past, the present fills my mind and I try to probe into the minds and hearts of these multitudes. Having long been imprisoned in the Secretariat of Delhi, I rather enjoy these fresh contacts with the Indian people. It all becomes an exciting adventure....

In the first general elections, over a million officials were involved. One hundred and seventythree million voters were registered through a house-to-house survey. Three-quarters of those eligible were illiterate. Elections were spread out over six months, from October 1951 to March 1952, and candidates of 77 political parties, apart from some independents, contested in 3772 constituencies. All observers, Indian and foreign, were agreed that it was fair.

The Manchester Guardian wrote on February 2, 1952:

The Working Committee of the Indian National Congress can draw pleasure from the extra-ordinary demonstration which India has given. If ever a country took a leap in the dark towards democracy it was India. Contemplating these facts, the Congress Working Committee may purr with satisfaction.

It is a measure of his faith in the wisdom of the people that the communal forces were badly beaten, securing only around six per cent of the vote and 10 out of a total of 489 seats as against the Congress’ tally of 364 seats. And this barely four years after the partition in which an estimated 600,000 people lost their lives in communal violence and another six million were displaced from their homes.

In Nehru’s understanding, democracy was necessary for keeping India united as a nation. Given its diversity, and differences, it could only be held together by a non-violent, demo-cratic way of life, and not by force or coercion. Only a democratic structure which gave space to various cultural, political, and socio-economic trends to express themselves could hold India together. “This is too large a country with too many legitimate diversities to permit any so-called ‘strong man’ to trample over people and their ideas.”

Nehru through his actions helped root parlia-mentary democracy in India. Even though he enjoyed tremendous popularity and power, he did not fall prey to plebiscitary democracy or populism, but strengthened representative institutions. He used his popularity to push for civil liberties and democratic culture. He played a major role in framing a democratic Consti-tution with civil liberties and adult franchise.

He treated Parliament with great respect and was often seen sitting patiently through long and often boring debates as an example to his colleagues and young parliamentarians. He spoke frequently in Parliament, and used it as a forum to reach his ideas and views to the people of the country. Despite the majority enjoyed by the Congress party, he ensured that Parliament reflected the will of the entire people, and a very large number of non-official bills were passed during his tenure, a practice that has declined since. Even when he was quite ill during the last few months of his life, he did not miss any session and would even insist on rising to his feet whenever he had to speak to maintain the decorum of the House.

He helped institutionalise the Cabinet system of government, a crucial part of parliamentary democracy, by resisting the tendency among his Cabinet colleagues to leave all policy-making to him.

He said democracy is something deeper than voting, elections or a political form of govern-ment: “In the ultimate analysis, it is a manner of thinking, a manner of action, a manner of behaviour to your neighbour and to your adver-sary and opponent.” A quote from a letter Nehru wrote to Bidhan Chandra Roy, Chief Minister of Bengal, on December 25, 1949, shows his understanding of how to work in a democracy:

It is not good enough to work for the people, the only way is to work with the people and go ahead, and to give them a sense of working for themselves.

Nehru understood that at the heart of democracy lay a respect for difference of opinion, for opposition. He said on June 2 1950:

I am not afraid of the opposition in this country and I do not mind if opposition groups grow up on the basis of some theory, practice or constructive theme. I do not want India to be a country in which millions of people say “yes” to one man, I want a strong opposition.

He opposed the banning of the Communist Party even though he was against their policy of sabotage and violence. He wanted that they should be countered by normal legal processes, and urged Chief Ministers to respect civil liberties.

When the Congress lost a by-election in Calcutta, Nehru wrote to N.R. Sarkar, acting Chief Minister of Bengal, on July 2, 1949: “We as a government, whether at the Centre or in the Provinces, have no desire to continue governing people who do not want us. Ultimately, people should have the type of government they want, whether it is good or bad.”

The forms of limited representative govern-ment which the British had granted lacked substance and life. Nehru transformed them into vibrant institutions. The experience of other ex-colonial countries where the first generation of nationalist leaders concentrated over time all power in their own hands, or were succeeded by military rulers, throws into sharp relief Nehru’s achievement. The success of parlia-mentary democracy in India, which we tend to take for granted, was the exception and not the rule in newly independent nations. He chided Nkrumah, the leader of Ghana, for promoting a personality cult by asking him on his first meeting: “What the hell do you mean by putting your head on a stamp?”

Nehru, to his credit, did not permit his enor-mous personal position to be institutionalised; on the contrary, he showed great deference to institutions such as Parliament, the judiciary (even when he disagreed), the Cabinet, the party.

He constantly educated the people during his continuous travels about the value of adult suffrage and their duty to discharge their right to vote with responsibility. His tremendous faith, a Gandhian legacy no doubt, in the capacity of the poor, unlettered people to understand issues and exercise reasoned choices was at the heart of his democratic convictions.

To quote S. Gopal,

"Achieved against daunting odds, democracy in India—adult suffrage, a sovereign Parliament, a free press, an independent judiciary—is Nehru’s most lasting monument."

For the sake of the health and longevity of Indian democracy, it is to be hoped that the incoming Prime Minister will acknowledge the contribution of the chief architect of this edifice of democracy, before whose physical form he bowed his head while entering its portals, and pay homage to him on his fiftieth death anniversary.

Prof Mridula Mukherjee retired as a Professor of Modern Indian History, Centre for Historical Studies, Jawaharlal Nehru University, New Delhi. She was earlier the Director, Nehru Memorial Museum and Library, Teen Murti Bhawan, New Delhi.

http://www.mainstreamweekly.net/article4958.html, 10 September 2017.

कोई टिप्पणी नहीं:

एक टिप्पणी भेजें