RANA SAFVI

THE WIRE, 07/04/2016

Not just Begum Hazrat Mahal and Rani Lakshmibai but dozens of women participated in active fighting against the British. Their stories are largely unrecorded.

|

| Begum Hazrat Mahal. Credit:Youtube |

April 7 marks the 137th death anniversary of Begum Hazrat Mahal, a woman who has gone down in history for her valour and courage in standing up to the might of the British forces in India’s first war of independence in 1857. This is as good a time as any to remember not the begum but also all the other women who sacrificed their lives in 1857 – many of whom are unknown and unheralded.

When we talk about women’s roles in 1857 we immediately think of Rani Lakshmibai and Begum Hazrat Mahal. But were these the only women who contributed to the struggle? There were women from the depressed classes (called dalit veeranganas by scholars), there were numerous bhatiyarins, or innkeepers, in whose inns plots were hatched by the rebels, aided by performers and courtesans who passed on news and information and even financed them.

But why is it that we hardly ever talk about these women? Is it because they were from the margins of society and so their sacrifices weren’t taken into account, or because no one propagated their stories of courage? Or is the reason for their “absence” that, in traditional patriarchal society, women were not seen as warriors?

The victors rewrote post-1857 history to suit their own interests. Eulogising or glorifying those who participated in the uprising against them wasn’t on their agenda, of course. The reason Jhansi ki Rani is so popular is because of the oral tradition and the dozens of folk songs that are still sung about her. The elite of Awadh kept Begum Hazrat’s legacy alive, though their ways didn’t prove to be as powerful as the folk songs. Nowadays comic books, especially the Amar Chitra Katha series, keep the legends of a select few alive.

But, apart for having their names registered in British records, most women remain unknown.

Begum Hazrat Mahal

|

| Begum Hazrat Mahal |

On May 10, 1857, the “sepoys” of Meerut rebelled against the British East India Company. Very soon, others joined them under the banner of Bahadur Shah II, the Mughal emperor, to whom the rebels gave the title Shahenshah-e-Hind. The rebellion became a full-fledged uprising against the British, with kings, nobles, landlords, peasants, tribals, and ordinary people fighting together. Yet historians tend to ignore, and to completely forget, the role of the women who came out of their homes and joined the men in fighting the Company Bahadur.

In Awadh, Begum Hazrat, wife of the deposed Nawab Wajid Ali Shah, took on the might of the East India Company and almost succeeded. The longest resistance to the British was offered by the begum and her trusted band of followers, Sarafad-daulah, Maharaj Bal Krishna, Raja Jai Lal and, above all, Mammu Khan. Her associates included Rana Beni Madho Baksh of Baiswara, Raja Drig Bijai Singh of Mahona, Maulvi Ahmad Ullah Shah of Faizabad, Raja Man Singh and Raja Jailal Singh.

She crowned her 11-year-old son Birjis Qadar the ruler of Awadh, under Mughal suzerainty, on June 5, 1857, after a spectacular victory by the rebel forces in the Battle of Chinhat. The British were forced to take refuge in the Lucknow Residency, a series of events that became famous as the Siege of Lucknow, while her diktat ran in Awadh as regent of Birjis Qadar.

William Howard Russell writes in his memoir My Indian Mutiny Diary: “This Begam exhibits great energy and ability. She has excited all Oudh to take up the interests of her son, and the chiefs have sworn to be faithful to him. The Begum declares undying war against us.”

The British made three offers of truce, even offering to return her husband’s dominions under British suzerainty. But for the begum, it was all or nothing. The longest and fiercest battles of the First War of Independence were fought in Lucknow. The begum ruled for 10 months as regent and had the biggest army of any of the rebel leaders that fought the British in 1857. The zamindars and peasants who had been reluctant to pay taxes to the British gave them to her voluntarily.

Wajid Ali Shah, when he left for Calcutta in 1856, had foreseen the begum’s fighting spirit and valour:

Gharo’n par tabahi padi saher mein, khude mere bazaar, Hazrat Mahal

Tu hi baais e aisho araam hai garibo’n ki gamkhwaar, Hazrat Mahal

[Calamity fell on the houses in the morn, my bazaars were looted, Hazrat Mahal

You alone are a source of comfort, O comforter of the poor, Hazrat Mahal]

She fought as long as she could and finally found asylum in Nepal, where she died in 1879. These lines are attributed to her:

Likha hoga Hazrat Mahal ki lahad par

Naseebo’n ki jail thi, Falak ki satayi

[It will be written on Hazrat Mahal’s grave

Starcrossed was she, oppressed even by the skies]

Jhansi ki Rani

|

| Jhansi ki Rani Laxmibai |

The bravery of Lakshmibai is the mainstay of many folk stories and songs of Bundelkhand. In the words of Rahi Masoon Raza:

Nagaha chup huye sab, a gayi bahar Rani

Fauj thi ek sadaf, us mein gauhar Rani

Matla-e-jahad pe hai gairat-e-Akhtar, Rani

Azm-e-paikar mein mardo’n ke barabar Rani

[Suddenly there was silence, here comes the Rani

The army was the oyster, the pearl was the Rani

In the battlefield, you could shame the stars, Rani

In bravery and courage, equal to men is the Rani]

Lakshmibai was born Manikarnika in the house of a brahmin priest in Varanasi. She was renamed Lakshmibai after marriage to Maharaja Gangadhar Rao of Jhansi in May 1842. After her husband’s death in 1853, Jhansi was annexed by the British under Lord Dalhousie’s infamous Doctrine of Lapse, as the British refused to recognise the right to rule of Laxmibai’s adopted son Damodar Rao.

Lakshmibai was forced out of the Jhansi fort and relegated to the Rani Mahal on a pension. But she was adamant that ‘mera Jhansi nahin dungi’ (‘I will not give up my Jhansi’) and sent several appeals to England against the annexation. All her appeals were rejected. In 1857, faced with attacks by neighbouring principalities and a distant claimant to the throne of Jhansi, Lakshmibai recruited an army and strengthened the city’s defences.

In the words of Makhmoor Jallundhari:

Laxmibai tere hathon mein tegh o sipar

Husn ki sari riwayat ki thi silk-e-gauhar

[Laxmibai the sword and shield in your hands

Is your jewelry, your string of pearls]

In March 1858, the British forces attacked Jhansi and were fiercely opposed. When they finally gained the upper hand, Laxmibai escaped from the fort with her son. She fled to Kalpi, where she joined Tatya Tope. Together, they captured Gwalior. But the British gained the upper hand yet again. The fighting shifted to the outskirts of Gwalior.

On June 17, 1858, during the fighting a Kotah-ki-Serai, five miles south east of Gwalior, the Rani, dressed in male attire, was shot at and fell from her horse.

Jhalkari Bai and the Durga Dal of Jhansi

|

| Jhalkari Bai |

Jhalkari Bai was part of the Durga Dal, or women’s brigade, of Jhansi. Her husband was a soldier in the Jhansi army, and Jhalkari too was trained in archery and swordplay. Her striking similarity to Lakshmibai helped the Jhansi army evolve a military strategy to deceive the British.

To elude the British, Jhalkari dressed up like her queen and took command of the Jhansi army, allowing Lakshmibai to escape unnoticed.

Jhalkari gave the British quite a shock when she was caught and imprisoned. According to legend, when the British discovered the impersonation, they released her and she went on to live a long life till 1890.

Jhansi, with its Durga Dal, saw the participation of many women who fought alongside their queen and sacrificed their lives for their kingdom. Some of the women we’ve found references to include Mandar, Sundari Bai, Mundari Bai and Moti Bai. These women were not content to wait on the sidelines and embrace widowhood.

Churi forwai ke nevta

Sindoor pochwai ke nevta

[You are invited to break your bangles

You are invited to wipe off the vermillion from your forehead]

Uda Devi, a crack shot and a warrior

|

| Uda Devi |

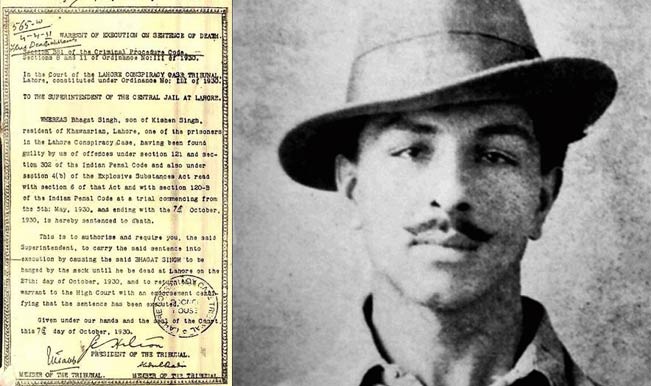

One of the fiercest battles in Lucknow was the Battle in Sikandar Bagh in November 1857. Sikandar Bagh was manned by the rebels and fell along commander Colin Campbell’s route as he marched to rescue the Europeans besieged in the Residency. A bloody battle ensued and thousands of Indian soldiers were killed.

A story goes that the British heard a crack shot, who was firing from atop a tree. It was only when they managed to fell the tree that they discovered that the person shooting was a woman, who was then identified as Uda Devi from the Pasi community. Her statue graces the square outside Sikandar Bagh in Lucknow today.

Forbes-Mitchell, in Reminiscences of the Great Mutiny, writes of Uda Devi: “She was armed with a pair of heavy old-pattern cavalry pistols, one of which was in her belt still loaded, and her pouch was still about half full of ammunition, while from her perch in the tree, which had been carefully prepared before the attack, she had killed more than half-a-dozen men.”

Koi unko habsin kehta, koi kehta neech achchut.

abla koi unhein batlaye, koi kahe unhe majboot.

[Some called them Africans, some untouchable.

Some called them feeble, others strong.]

Many African women were employed in the court of the Awadh nawabs to guard the harem. They too perished in the battles in Lucknow during 1857.

A particular feature of the great uprising was the participation not just of women from royal and noble backgrounds but of women from depressed classes too. Another dalit veerangana was Mahabiri Devi from the village of Mundbhar in the district of Muzaffarnagar. Mahabiri formed a group of 22 women, who together attacked and killed many British soldiers in 1857. The women were all caught and killed.

Azizun Bai

|

| Azizun Bai |

But perhaps one of the most fascinating stories is that of the courtesan Azizun Bai of Kanpur.

Kanpur saw fierce battles between the forces of Nana Sahib and Tatya Tope against the British.

Tere yalghar mein tameer thi takhrib na thi

Tere isar mein targheeb thi taadeeb na thi

Your war cry was one of construction, not destruction

Your sacrifice was to inspire, not admonish

– Makhmoor Jallundhar

Colonial and Indian historians have mentioned Azizun’s role during the battles of Kanpur. She had personally nothing to gain and no personal grudges, unlike many of the other women who had joined in the uprising. She was simply inspired by Nana Sahib.

Her memory is still alive among the people of Kanpur. She dressed in male attire like Lakshmibai and rode on horseback with the soldiers, armed with a brace of pistols. She was part of the procession the day the flag was raised in Kanpur to celebrate the initial victory of Nana Sahib.

Lata Singh writes in her article “Making the ‘Margin’ Visible” that Azizun was a favourite among the sepoys of the 2nd cavalry posted in Kanpur, and was particularly close to one of the soldiers, Shamsuddin. Her house was a meeting point of the sepoys. She also formed a group of women, who went around fearlessly cheering the men in arms, attended to their wounds, and distributed arms and ammunition. She made one of the gun batteries her headquarters for this work. During the entire period of the siege of Kanpur, she was with the soldiers, who she considered her friends, and she was always armed with pistols herself.

Other valiant women

Rudyard Kipling’s ‘On the City Wall’ refers to the anti-British activities of the courtesans during 1857.

In fact, many of the courtesans’ kothas were meeting points for the rebels. Post 1857, the full might of the British Empire descended on these kothas. The courtesans who had been the repositories of old culture and fine arts were relegated to the status of common prostitutes and their vast properties seized.

The Muzaffarnagar area in western UP saw the active participation of women. Some of the names of the women rebels are Asha Devi, Bakhtavari, Habiba, Bhagwati Devi Tyagi, Indra Kaur, Jamila Khan, Man Kaur, Rahimi, Raj Kaur, Shobha Devi and Umda, all of whom sacrificed their lives in active fighting.

According to the records, all these women, with the exception of one Asghari Begum, were in their 20s. They were hanged and, in some cases, burnt alive.

There were two other queens whose kingdoms were the victims of the Doctrine of Lapse and who rose against the British. They were were Avantibai Lodhi of Raigarh and Rani Draupadi of Dhar.

Sadly, not much has been written about these other brave freedom fighters of 1857 and resources on them are scarce. One such resource is Shamsul Islam’s article ‘Hindu-Muslim Unity: Participation of Common People and Women in India’s First War Of Independence,’ which mentions the names of many women who are today only relegated to the pages of the 1857 records.

It is time India remembered, and saluted, these brave women

Rana Safvi is a writer, and author of Where Stones Speak: Historical Trails in Mehrauli, First City of Delhi